DOI: https://doi.org/10.47133/respy41-23-2-13

BIBLID: 0251-2483 (2023-2), 294-316

Introduction to contemporary economics in Paraguay: agro-livestock

production and economic elites

Introducción a la

economía contemporánea en Paraguay: producción agropecuaria y éliteseconómicas

Magdalena López1 ![]()

1Universidad de Buenos Aires,

Grupo de Estudios sobre Paraguay. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

|

Correspondencia:

maguilopez84@gmail.com ·

Editor responsable: Carlos

Anibal Peris ·

Revisor 1: Ilda Mayeregger ·

Revisor 2: Gerardo Jara

|

Abstract: This paper analyzes the forms of wealth reproduction and the concentration of wealth in Paraguay, strongly centered on the export of primary products, especially associated with soybean and cattle production in large-scale farms. It briefly reconstructs the political and state development that enables the wealth production environment, identifying the productive associations (gremios) that represent the interests of the most prolific sectors of the primary export economy. It also proposes a comparative look at poverty and inequality. The article compares the National Agricultural Censuses of 1991, 2008 and 2022, providing some analytical lines around land tenure, variation in the products and farm sizes. In addition, it analyzes data from the National Institute of Statistics to investigate monetary poverty and income inequality. Finally, it also draws on in-depth interviews with relevant actors within the sectoral associations.

Keywords: Paraguay; contemporary economy; productive Gremios; economic elites.

Resumen: Este trabajo analiza las formas de reproducción de la riqueza en Paraguay, fuertemente centrada a la exportación de productos primarios; y a la concentración de la misma, especialmente asociada a la producción de soja y ganado en fincas de alta escala. En la misma línea, reconstruye brevemente el desarrollo político y estatal que permite el entorno de producción de riqueza, identificando a los gremios productivos que representan los intereses de los sectores más prolíficos de la economía primaria de exportación. Además, propone una mirada comparativa con la contracara de este modelo, indagando en la pobreza y en la inserción económica de los demás actores económicos, ajenos a las dinámicas agroexportadoras. El artículo compara los Censos Agropecuarios Nacionales de 1991, 2008 y 2022, aportando algunas líneas analíticas en torno a la tenencia de la tierra, la variación en los productos seleccionados y los tamaños de las fincas. Además, analiza datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística para indagar en pobreza monetaria y desigualdad de ingresos. Finalmente, también se nutre de entrevistas en profundidad a actores de relevancia dentro de los gremios sectoriales.

Palabras clave: Paraguay; economía contemporánea; gremios productivos; elites económicas.

Contributions to the studies of wealth on Paraguay

Paraguay is a relatively marginalized case study in Latin American studies. When analyzing the conformation and political strategies of economic elites in Latin America, studies of central countries –such as Mexico, Colombia, Argentina and Brazil, characterized by a more developed national industrial pole despite the relevance of the agro-export sector– as well as countries whose productive structures have been transformed –such as Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile and Venezuela, whose gas, mining and oil industries have changed the conformation of elites– have been predominant. Research on the emergence, consolidation, intervention in public life, and influence of the business elites has been conducted in various countries, and a number of solid comparative studies have been produced. Nevertheless, a number of gaps persist. In Paraguay, in particular, studies on the country’s business elite have tended to focus on exposing agribusiness and livestock farming entrepreneurs’ high concentration of power, land and wealth and their violence towards the peasantry (Ezquerro, Cañete, 2020; Fogel, 2020; Hetherington, 2011; Palau, 2010; Riquelme, 2003).

An in-depth analysis of the Paraguayan case allows us to shed light on the forms that wealth takes in a state that plays a secondary role in the dynamics of global and regional capital, and also depends on the capitalist development of central and peripheral countries. Notwithstanding this context, the Paraguayan elites have developed trajectories of power that are neither archaic nor disconnected, but are geographically, culturally, and politically intertwined. This paper, based on in-depth interviews and ethnographic observation, reconstructs the perceptions of Paraguayan economic elites organized in agribusiness and farming associations (gremios[1]), in order to identify their representations of wealth (closely associated with land as a productive factor) and the state (especially understood in terms of its capacity to create, impose, and collect taxes).

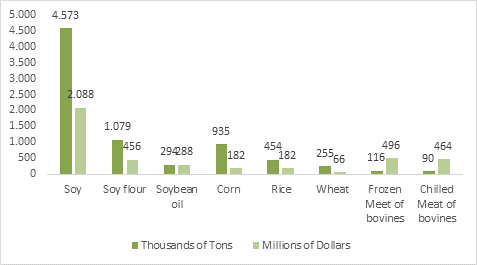

Due to its historical construction, its insertion in the world market with a strongly defined profile as a producer and exporter of raw materials, as well as its productive matrix, which positions land as one of the most profitable assets, Paraguay has developed an economy characterized by agricultural exports (historically cattle, cotton and yerba mate), especially since commodity prices exploded on the global market, which positioned cattle, soybeans, wheat and corn internationally– (see Figure 1), and electric energy obtained from two of its hydroelectric plants, one jointly managed with Argentina (Yacyreta) and the other with Brazil (Itaipu). According to the Vice Ministry of Mining and Energy (2020), in 2019, 64% of the energy produced by Paraguay’s dams was exported (just under 50000 GWh), 9% was lost during distribution or transmission, and almost 26% was used by the domestic market. The rest was used to run the dams.

Figure 1. Main Exports Commodities in 2021 by Thousands of Tons and Millions of Dollars.

Source: Self-made based on data provided by the

Ministry of Finance (2022).

The fact that the Paraguayan economy depends on international capital, lacks technological development, and is heavily reliant on neighboring countries in order to access regional networks, significantly limit the country’s productive potential and its capacity to generate more socially inclusive production chains (Rojas, 2015). Arce and Rojas (220) emphasize Paraguay’s subordination to Argentina because of its dependence on the river system shared with neighboring countries. These authors also emphasize the fact that the country’s export basket, its lack of industrial development, and its reliance on imports make the country more vulnerable to external shocks and impacts.

An analysis of Paraguay’s productive sectors between 2000 and 2019, shows its industry was in decline, while the country’s primary and service sectors boomed (Arce and Rojas, 2020). By prioritizing a telluric idea of production tied to land ownership, personal connections and strong alliances between parties and elites, Paraguay has experienced a sustained economic growth over the past fifteen years, based on the extraction and export of raw materials (Arce and Rojas, 2020).

Paraguay is also characterized by its policy of radical economic and financial openness, which encourages imports over industry. The absence of an industrialization process as strong as that of neighboring countries enables us to identify, firstly, the reasons why industry was marginalized in comparison with agriculture and farming exports, and why it did not benefit from the state’s protectionist policies (Masi, 2016); and secondly, the consolidation of the agribusiness and farming elites as key actors in Paraguay’s domestic politics and economy, as well as the extent of their power.

The relevance of these economic actors is reflected in the centralized power of their business associations, or guilds, which are bodies for consultation and mandatory negotiation by the state, and, at the same time, strong resistance to modifying the tax burden and to the stability of governments that they consider contrary to their interests.

The connections and networks among Paraguay’s political and business elite blur the line between business and politics and make it hard to discern whether political capital morphed into economic capital or vice versa (López, 2020; Rojas, 2014). Moreover, over the past decade it has become increasingly difficult to distinguish between the business elites whose accumulated capital and lobbying power derive from (tolerably) legal business activities, those who acquired wealth as a result of corrupt practices (as evidenced in studies that analyze the enrichment of public officials based on their sworn statements of assets and their incursion into the business world), or those who have engaged in openly criminal activities (for example, laundering the proceeds of criminal activities, such as drug trafficking)[2].

The power of the business elites stems from their status in the business world, from their political connections, which is very often mediated by partisan relations, and from the connections they establish with a state that plays a diminished role in the provision of social welfare and has allowed the private sector to lead the country’s development process and become a key decision-maker, thereby becoming an actor to be consulted, as well as the stabilizing (or destabilizing) axis for successive administrations.

Paraguay’s low tax burden hinders meeting tax collection targets, which in turn, prevents the state from taking a leading role in terms of the provision of social services, enforcing the law and sanctioning violations, and guaranteeing social, economic, and productive rights. And this void left by the absence of the state is filled by business associations that perform tasks that the state is usually responsible.

Parties, politics, and agro-farming economic elites

The relationship between the economic elites and the state is strongly mediated by two traditional political parties, the Partido Colorado (Asociación Nacional Republicana or ANR) and the Partido Liberal Radical Auténtico (PLRA), which have headed the executive and achieved a majority in Congress since the country’s return to democracy in 1989. The low rotation of Congressmen and guilds’ representatives has stabilized relations (formal and informal) between the political and economic elites (López, 2020).

Paraguay is one of the few countries in the region that continued to be ruled by bipartisan politics[3]. The ANR and the PLRA, both of which were founded in 1887, have held the majority in Congress since the return of democracy, and all Paraguayan presidents between 1989 and 2008, and from 2013 to the present, have belonged to the ANR.

The Partido Colorado also ruled Paraguay during the dictatorship, backing General Alfredo Stroessner, with support from the armed forces, who seized power in 1954 and was overthrown by Andrés Rodríguez, another general, in 1989. Rodríguez also belonged to the ANR and also belonged to the country’s military, ruling and business elite.

During Stroessner’s thirty-five yearlong dictatorship, Paraguay saw the emergence of a series of political and business actors who consolidated their power through their closeness to the regime and benefited from access to ill-gotten lands (tierras malhabidas in Spanish). These lands, which were illegally obtained, have remained in the hands of actors linked by family ties, membership of the two ruling parties or to the business elite (Guereña and Rojas Villagra, 2016).

Despite the existence of this group of privileged business actors, other business sectors distanced themselves from the Stroessner regime, especially towards the end of his de facto rule, and managed to influence the legal framework built during the post-dictatorship years (Ortiz and Rojas, 2019). This means they were also able to gain leverage within the political sphere.

The ANR, and more precisely the sector related to the Stroessner regime, led the government during the transition to democracy. It was not until 2003 that Nicanor Duarte Frutos, an ANR candidate who did not belong to the circle that gained wealth or power under the Stroessner regime, was voted into office.

In 2008, Fernando Armindo Lugo Méndez, a former bishop, headed a multi-party alliance that included the PLRA, thereby becoming the first president who did not belong to the country’s bipartisan structure, to take office after 61 years of colorado dominance. He would also be the first president identified by the business elite as a potential threat to Paraguay’s prevailing business model.

The Lugo administration was cut short on June 2012, by an impeachment (popularly considered a coup run by the Parliament), which was supported by the country’s most prominent agribusiness associations. The period of Lugo was completed by the vice president, Federico Franco, from PLRA. In 2013, the expulsion of the former bishop entailed the return of the Partido Colorado to the presidency led by Horacio Cartes, a member of the business elite. Cartes, who had no previous history of involvement in politics, joined the ANR, financed his own campaign as well as the party –with the profits reaped from his business career– and won the elections with a sweeping majority.

The ongoing presence of the traditional parties and the permanence of members of the political elite in parliamentary positions for so long (guaranteed by indefinite Congressional reelection) have encouraged relationships between members of different elites. Several studies (Guereña and Rojas Villagra, 2016; Palau, 2010) have shown that Paraguay’s political and economic elites are closely intertwined, with the same actors often playing a key role in both the business sector and politics.

This trend is clearly illustrated by the presence of members of the business elite, especially from the agriculture and farming sectors, in Congress and Executive branch, as well as the record number of businessmen who are directly involved in politics or provide services to the State, often through influence peddling or fraudulent bids (López, 2020). However, we acknowledge that the Paraguayan elites are bound together by close ties, and often play multiple roles, but they don’t overlap completely. The fact that ex-bishop Fernando Lugo or Nicanor Duarte Frutos, of the Partido Colorado, were voted into office, shows there are still political actors who are not directly intertwined with the business elite. Likewise, the fact that Cartes was voted into office demonstrates the need of these political outsiders to get closer to the traditional parties, which often play the role of mediators in the rotation of elite figures.

Despite this closeness, business associations state they are non-partisan in their statutes and charters. However, although these actors are not bound together by any legal ties, a number of informal channels have brought them closer together (Fairfield, 2015) and have created a variety of positions, thus enabling us to map out the same actors –business or family representatives–across different spheres of power. These ties are openly acknowledged by business leaders both in their public statements as well as press interviews. The business elites gain preferential access to the sphere of political power, both through their lobbying mechanisms as well as their direct connections to members of the political elites. This is compounded by the business sector’s self-perception of the key role it plays in the provision of security, crime prevention, healthcare and productive development, which has led it to justify its control of and delegitimization of the State, as well as its hierarchization in relation to other social groups, especially those that dispute its legitimacy, such as the peasants.

Economics, wealth, and exports in contemporary Paraguay

Paraguay has become a macro economically orderly state, which has consolidated growth even when its neighbors have faced recession[4]. With a historically stable currency, the guarani, and a very low tax burden, Paraguay has positioned itself in recent decades as a desirable destination for businessmen and economic groups from neighboring countries who wish to extend their productive and/or speculative ventures.

Although services and trade are the country’s main sources of employment (INE, 2022), the most profitable are those related to agricultural and farming export production. In 2020, soy was Paraguay’s main export crop, followed by energy and meat (INE, 2022).

Within the area designated for agriculture, soy is the most cultivated crop. Soybean occupies 3539808 hectares out of the total 4185598 hectares destined to temporary crops, equivalent to 84.57% (CAN, 2023).

Regarding land organization, according to the National Agricultural Census of 2008 (CAN) –compared with data from 1991–, the number of productive farms decreased. Table 1 shows that by 2022, the outcome is different than the previous census. While the number of farms smaller than one hectare increased, those ranging from 1 to 20 decreased. Those of more than 20, more than 50, more than 100, more than 200 and more than 500 ha also increased. Those of more than 1000 and more than 5000 decreased and those of the largest scale (more than 10,000) increased slightly.

Table 1. Number of Farms According to Size in The National Agricultural Census. 1991, 2008 and 2022.

|

Size |

1991 |

2008 |

2022 |

|

Unspecified |

7.962 |

774 |

- |

|

Less 1 ha |

21.977 |

15.586 |

25.300 |

|

1-5 ha |

92.811 |

101.643 |

96.509 |

|

5-10 ha |

66.605 |

66.218 |

65.363 |

|

10-20 ha |

66.223 |

57.735 |

52.040 |

|

20-50 |

31.519 |

22.865 |

24.963 |

|

50-100 ha |

7.577 |

6.879 |

8.651 |

|

100-200 ha |

4.279 |

5.234 |

5.743 |

|

200-500 ha |

3.503 |

5.251 |

5.626 |

|

500-1000 ha |

1.525 |

2.737 |

2.778 |

|

1000-5000 ha |

2.356 |

3.443 |

3.262 |

|

5000-10000 ha |

533 |

684 |

645 |

|

More 10000 ha |

351 |

600 |

617 |

|

Total |

307.221 |

289.649 |

291.497 |

Source: Self-made based on data provided by the Ministry of Farming and Agriculture (2009, 2023).

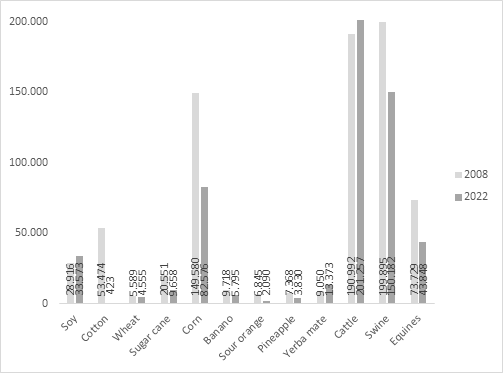

While the number of soy farmers remained relatively stable, the planted surface area quadrupled between 1991 and 2008, and continued growing to 2022. In contrast, cotton showed a decrease in terms of both land ownership and cultivated area, which can be attributed to the increase in land used for soy and corn production (See Table 3). The same drop, both in cultivated area and in the number of producers, was seen in fruits and yerba mate in 2008 (Ministry of Agriculture and Farming, 2009). However, these data rebounded timidly by 2022, probably associated with the increase in smaller farms.

Cattle farming experienced a similar pattern to soy production, but with a lower degree of concentration. While the number of producers decreased, the number of cattle increased. The increment of livestock heads is stable between 1991 and 2022 (as seen in Table 2).

Table 2. Cultivated Area by Crop in Hectares (ha), Livestock (heads), According to the National Agrarian Census. 1991, 2008 and 2022.

|

Product |

1991 |

2008 |

2022 |

|

Soy |

552.657 |

2.463.510 |

3.539.808 |

|

Cotton |

414.691 |

66.256 |

18.854 |

|

Wheat |

153.837 |

381.028 |

433.144 |

|

Sugar cane |

55.879 |

81.830 |

90.333 |

|

Corn |

243.215 |

858.101 |

1.192.210 |

|

Banana |

9.030 |

7.434 |

15.960 |

|

Sour orange |

10.354 |

6.938 |

2.780 |

|

Pineapple |

2706 |

5004 |

5.121 |

|

Yerba mate |

26.515 |

18.305 |

38.724 |

|

Cattle |

7.626.617 |

10.496.641 |

13.241.944 |

|

Swine |

1.003.880 |

1.072.655 |

1.801.460 |

|

Equines |

319.921 |

283.804 |

225.439 |

Source:

Self-made based on data provided by the

Ministry of Farming and Agriculture (2009, 2023).

Based on the 2008 CAN, it was possible to demonstrate statistically the increase in soy farming and land concentration that has occurred in the Paraguayan countryside (Ezquerro-Cañete, 2020; Fogel, 2020; Hetherington, 2011; Riquelme, 2003). Corn has also become an increasingly important crop.

Not only has the amount produced and the size of farms increased, but the number of producers (farms) has decreased for almost every crop, except soybean, as well as cattle farming (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of Farms According to the National Agrarian Census. 2008 and 2022.

Source: Self-made based on data provided by the Ministry of Farming and Agriculture (2009).

Except for soybeans, yerba mate and cattle, farms dedicated to other productions suffered a decrease between 2008 and 2022.

With corn, in particular, there has been a significant decrease in the number of farms but an increase in the cultivated area (from 768,903 in 2008 to 1,192,210 in 2022). This may be due to crop intensification, mechanization, and the acquisition of genetically modified seeds.

The social consequences of this model are clear, condemning a significant sector of the population to poverty (INE, 2022b; Ortiz Sandoval, 2020; Fogel, 2019). While the rural business sector has expanded its investments, peasants have been increasingly displaced in the absence of industrialization policies requiring labor (Fogel, 2019), and have been forced to migrate to the cities, where there are few employment opportunities.

The majority of the land, properties, opportunities and income are concentrated in the hands of business owners and large agricultural landowners, and their interactions with the state are very relevant (Ortiz Sandoval, 2020).

Between 1997 and 2021, there has been a 20% decrease in income inequality in Paraguay, as evidenced by the reduction of the Gini coefficient from 0.542 to 0.431 (INE, 2021a).

This same trend is evidenced by the decline in the incidence of multidimensional poverty (comprised of the dimensions of labor and social security; housing and services; health and environment; and education) between 2016 and 2021, which went from 34.28 to 20.76 (INE, 2021b). However, the impact is less perceptible if we review the evolution of monetary poverty, which went from 28.86 to 26.89 (INE, 2021b), which would indicate that the transformations on income have not been substantial, although there have been improvements in the other dimensions of the phenomenon.

One of the persistent factors in multidimensional poverty is the lack of contributions to pension funds, associated with labor informality that has not diminished over time. By 2021, 64.2% of Paraguay's workers were classified as informal, and in rural areas this figure rose to 75%. If we focus on the elderly population, the number climbed to a worrying 79.3% (INE, 2021c).

During the same period, unemployment reached 4.8% of women and 9.8% of men, and poverty reached 26.9% of the population, with a 3.9% extreme poverty rate (INE, 2022b).

Most workers are employed in activities related to commerce, hotels and restaurants, followed by community, social and personal services, and in third place, agriculture, livestock, forestry, hunting and fishing (INE, 2022a).

Although these are the activities that absorb the greatest amount of labor, the ones that concentrate the greatest amount of profitability are those related to agro-livestock production for export. In 2020, soybean seed represented the largest exportable item, followed by energy and then meat. If, in addition to seeds, flours and oils are included, soybeans accounted for around 40% of the exports registered in 2020 (INE, 2022a).

Given this scenario of wealth associated with agricultural and farming production and displaced peasants, land disputes emerge as a key characteristic of Paraguay’s capitalist development, not only in terms of tenure, concentration and production, but also as a result of the expansion of the area used for agriculture and farming, which has encroached the area dedicated to natural resources (such as native forests and nature reserves)[5] and has pushed the limits of the country’s climate conditions. An example of this are the so-called “pioneers”, rural entrepreneurs who promote and develop livestock farming in the Paraguayan Chaco area, where limited access to water and the persistence of hostile climates pose a challenge. In the same area and facing the same limitations, Mennonite cooperatives have developed a thriving dairy cluster that has successfully included small producers.

Land tenure problem is the result of a specific process of land grabbing (legally or illegally, depending on the historical moment and the specific case), often associated with the close ties between business and political elites who grant benefits to the former, as well as legal loopholes or negotiations within the framework of the law.

Land is such an important factor in productive, economic, commercial, political, and cultural terms that the Constitution in force since 1992 enshrines the right to agrarian reform (articles 114, 115 and 116). However, although the Magna Carta establishes that the state should guarantee the fulfillment of this right and grants peasants rights over large unproductive estates, in practice, land grabbing continues. This tension was characterized by Fogel, Paredes and Valdez (2022) as a paradox between progressive constitutional mandates and the application of regressive laws. According to these authors, Paraguay’s legal system provides a veneer of legality but applies civil code regulations in a fraudulent manner, benefiting large producers, in favor of the land grabbing regime, to the detriment of indigenous and peasant communities. As well as enjoying legal and political benefits, this productive sector benefit from an extremely favorable tax regime. It is therefore clear that the Paraguayan state is unable to achieve a tax collection that allows for growth and distribution (Arce and Rojas, 2020), which means indirect and regressive taxes, especially the Value Added Tax (IVA, in Spanish), have prevailed. The sectors that generate the greatest profits are those that are taxed comparatively less and, moreover, those that benefit the most from IVA refund regimes (Guereña and Rojas Villagra, 2016). This characterizes not only Paraguay, but all Latin American and Caribbean countries. However, the Paraguayan case is particularly striking due to the tax conditions enjoyed by the agricultural and farming elites, which have successfully lobbied successive governments in order to avoid the imposition of new taxes or tax increases, as well as guaranteeing IVA refund mechanisms for export activities.

Although Paraguay has undergone major changes in terms of its tax burden as well as the impact of taxation since the 1990s, which has implied a progressive although slow increase in the burden, it remains lower than the regional average and the lowest in MERCOSUR area (Arce and Rojas, 2020; De Iturbe, 2017; Florentín Portillo, 2021, Borda and Caballero, 2018). Paraguay’s tax burden is 9.9%. Personal income tax is 10%, as is corporate income tax (the lowest in Latin America) and IVA (second lowest in Latin America, after Panama at 7%) (Arce and Rojas, 2022; Borda and Caballero, 2018).

As indicated by all the gremios agroganaderos interviewed, taxes are considered adequate. Also in the industrial sector, businessmen interviewed by Masi (2016) stated that taxes “se pagan bailando”, i.e. they do not represent any effort.

“The future of the country is in the countryside”: Gremios and its representations

To complement this article, we will briefly analyze the interviews conducted with members of the Asociación Rural del Paraguay (ARP, for its acronym in Spanish), la Cámara Paraguaya de exportación de soja y oleaginosas (CAPECO), la Unión de Gremios de la Producción (UGP) y el Centro Yerbatero Paraguayo (CYP). These interviews, dating from the years 2022 and 2023, have been analyzed in previous works in which we inquired about the politicization of the sector inward and outwardly (Lopez, in press), so in this case we will present general readings.

The in-depth interviews were conducted in all cases within the gremios in Asunción and Gran Asunción, except for the one with the Centro Yerbatero, which was carried out in a public space because its main building is in Itapúa. This corpus of interviews is part of a long term work in which more than 65 members of the economic and political elites of Paraguay have been interviewed.

In this section we are interested in describing the discursive similarities presented by these business associations in terms of their assessment of the land problem in Paraguay and the role of the State. Both elements are very close to what we previously described regarding land concentration, and the low tax burden on the sector.

The gremios emphasize the importance of exploiting land for production purposes; which is in line with the notion that the countryside is the guarantee of growth and progress, expressed both in the ARP’s slogan, “The future of the country is in the countryside”, as well as in the UGP’s, “Paraguay grows thanks to the work of the countryside” and the vision of the CYP’s “Ensuring the strengthening of the yerba mate sector, contributing to the economic development of the country”.

The dispute over land is determined by two intersecting accusations: that of ill-gotten tenure made against the landowners, and that of illegal occupation and violation of private property made against the various peasant and landless movements that occupy certain lots, demanding the rights granted under the agrarian reform. Gremios, on one hand, demand formal means of production, legal land tenure and the means to develop their work, but on the other they stress the political responsibility of the land occupation carried out by the peasants.

Hetherington (2011) explains that, in addition to ill-gotten lands, there are problems with precarious lots and the proliferation and overlapping of ownership documents, which makes it even more complex to distinguish owners and titleholders. This becomes more complicated when we investigate who are the people who report these irregularities, many of which derive from circles of politicians in public office (current or past), a practice that has not been eradicated since the stronista dictatorship.

The interviewed leaders of UGP, CAPECO and ARP discursively rejected the untitled lands that large producers may have, even if some of them are even in their associations.

Rural business associations claim that unlike farmers who adapted to modern times, the peasants who occupy land have a close relationship with a number of more recently created political parties, which have a less conservative profile than the traditional ones. As a UGP leader succinctly put it, “there are politicians who want to campaign and collect votes on other people’s land and promote [land] invasions.”

In this context, gremios are regarded as legitimate and even preferable means to prevent occupations, prevent civil unrest, ensure the rule of law, support producers who report land invasions and intervene both vis-à-vis the state and the organized peasantry that is willing to invade productive or unproductive farms. The chairman of CAPECO summed it up as follows: “When an attempted land invasion occurs, we immediately verify where they [the invaders] are from, what possessions they have, and the authorities work on the issue in order to find a place where they can be relocated, if needed, or ascertain if they belong to established settlements and are returning.”

The forceful role played by the gremios in terms of preventing these practices, as well as fighting against cattle smuggling and cattle rustling, fuels the notion that they are key actors that provide services that the state ought to provide. In this way, they justify their rejection of the tax increase and reaffirm their demand that the State have them as intermediaries and advisors.

On this point, Paraguay’s low tax burden is tolerable for the business elite. However, business leaders acknowledged that sometimes taxes can become inconsistent and they need to control the state on this topic. As a CAP leader told us: “We need to constantly assess the situation and strike a balance. We don’t just seek the business sector’s best interests; the law needs to support Paraguay’s sustainable development.”

In this sense, Paraguayan businessmen are not opposed to the current tax burden nor to taxation per se; they expect to be consulted on taxation and that no decisions are made without their agreement. “Successive democratic governments share a key characteristic: all major changes were made with the acquiescence of the private sector, in some way,” says a national ARP leader.

Conclusions

Paraguay, which has an open economy that is attractive for international investors, a low tax burden, a mostly indirect and regressive tax regime, and is led by a powerful elite of agricultural and farming exporters, has inserted itself in the regional and world market as a supplier of raw materials and has managed to consolidate its production in the regional context of the commodities boom. The relationship between businessmen and politicians has been marked by the concentration of power in the hands of a small number of political and business representatives, as well as the lack of elite renewal and their tendency to perpetuate themselves in power, which means there is a multi-positional dynamic between the business and the political elite, even though the overlap is not total. Traditional political parties, especially the Partido Colorado, act as intermediaries or connections between these elites, should they wish to invest in other areas.

The business elites also have voluntary business associations that group them together by sector. These associations are characterized by the provision of more specific services to their members, but above all by their capacity to build networks and connections, by their internal and external politicization, and by their lobbying and connections to the parties, the state and the government.

Firstly, we identified the most important sector of the economy, the agro-livestock sector, and mapped its most important business associations.

In this context, taxes are seen as reasonable, but it is up to the agribusiness associations to ensure the state exerts a tight control over these resources in order to ensure accountability and guarantee that public spending yields what they regard as quality results that encourage progress and development.

With regard to land, the associations identify existing irregularities in terms of land tenure, although in reality they focus more on the problem of occupations by landless peasants claiming productive plots of land. They argue that this practice stems from a political problem and that certain social and partisan groups have taken advantage of the peasants and indigenous groups occupying the land.

The economic opening, the state’s secondary role in terms of providing public services, and the importance of private investment have led the various associations –especially those related to the exploitation, commercialization and export of agricultural and farming products– to participate in activities beyond their remit, going as far as providing a number of security services, animal and crops health inspections, infrastructure development, and mediation in legal disputes, among others. This active role, compounded by the business sector’s self-portrayal as the only actor driving progress and growth in Paraguay, has strengthened the perception of private sector as the actor that can most appropriately decide on a reasonable tax burden and how tax revenue ought to be spent.

Thus, consolidating over the years, the model of land grabbing and monopolization of agro-wealth is fed by an underfinanced State, which does not execute the works or provide the necessary services to guarantee inclusive development. The role of economic development promoter is discursively occupied by the unions, which only lobby and pressure to consolidate their sectoral interests. The permanence of their leaders and their closeness to the traditional parties provide them with preferential spaces to influence the government.

Referencias

Arce, L., & Rojas, G. (2020). "Paraguay [369-426]". In Cálix, Á., & Blanco, M. (coord.) Los desafíos de la transformación productiva en América Latina. Perfiles nacionales y tendencias regionales. Volume II. Cono Sur. México: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Borda, D., & Caballero, M. (2018). Una reforma tributaria para mejorar la equidad y la recaudación. Asunción: CADEP.

Cavarozzi, M., & Abal Medina, J.M. (2002). El Asedio a la política: los partidos latinoamericanos en la era neoliberal. Buenos Aires: HomoSapiens Ediciones.

De Iturbe, C. (2017). Equidad tributaria. Asunción: Decidamos.

Ezquerro-Cañete, A. (2020). "La lucha de clases por la tierra y por la democracia en Paraguay". Estudios críticos del desarrollo X(18): 97-144.

Fairfield, T. (2015). Private Wealth and Public Revenue in Latin America. Business Power and Tax Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

FAO (2020). Global Forest Resource Assessment 2020. Main report. Italia. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8753es

Florentín Portillo, J.L. (2021). "Conocimiento y cumplimiento tributario en el Paraguay desde la perspectiva del sector empresarial". Saeta digital Contabilidad, Marketing y Empresa 6(1): 24-44.

Fogel, R. (2019). "Desarraigo sin proletarización en el agro paraguayo". Íconos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales (63): 37-54. https://doi.org/10.17141/iconos.63.2019.3423

Fogel, R. (2020). "Dimensiones relevantes para el estudio del régimen agroalimentario neoliberal". Revista Novapolis 16: 11-27. http://pyglobal.com/ojs/index.php/novapolis/article/view/111/117

Fogel, R., Paredes, R., & Valdez, S. (2022). "The Paradoxes of a Progressive Constitution and Neoliberal Food Regime". In Chadwick, A., Lozano-Rodríguez, E., Palacios-Lleras, A., & Solana, J. (Eds.). Markets, Constitutions, and Inequality (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003202257

Global Forest Watch (2022). Forest monitoring. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/PRY

Guereña, A., & Rojas Villagra, L. (2016). Yvy Jára. Los dueños de la tierra en Paraguay. Asunción: OXFAM.

Hetherington, K. (2011). Guerrilla Auditors: The Politics of Transparency in Neoliberal Paraguay. Duke University Press.

INE (2022a). Compendio estadístico 2020.

INE (2022b). Principales resultados de pobreza monetaria y distribución de ingresos 2021.

INE (2021a). Desigualdad de Ingresos. EPH 1997/98 al 2021. Serie comparable. Encuesta Permanente de Hogares 1997/98-2016 y Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua 2017-2021.

INE (2021b). Índice de pobreza Multidimensional. 2016-2021. Encuesta Permanente de Hogares 2016 y Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua 2017-2021.

INE (2021c). La ocupación informal en Paraguay. Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua 2021

López, M. (2020). "Traditionalism in the contemporary political elite of Paraguay". European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (110): 59–77. http://doi.org/10.32992/erlacs.10522

López, M. (in press). "Mucho más que solo económicos. La construcción política de los gremios agroganaderos en Paraguay". Latin American Perspectives, Especial Issue

Long, T., & Urdinez, F. (2020). "Status at the Margins: Why Paraguay Recognizes Taiwan and Shuns China". Foreign Policy Analysis 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/oraa002

Martens, J. (2019). "Entre grupos armados, crimen organizado e ilegalismo: Actores e Impactos Políticos y Sociales de la Violencia en la Frontera Noreste de Paraguay con Brasil". Abya-Yala: Revista sobre Acceso a la Justicia y Derechos en las Américas 3(3): 65- 87. https://doi.org/10.26512/abyayala.v3i3.30201

Masi, F. (2016). Ser industrial en el Paraguay. 15 historias recientes. Asunción: CADEP.

Ministry of the Treasury (2022). Foreign Trade Report. Undersecretary of State for Economics. National Government.

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (2020). Statistical synthesis. Agricultural production. 2019.

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (2009). National Agricultural Census, 2008.

Moriconi, M., & Peris, C. (2018). "Análisis sobre el tráfico de drogas en la ciudad de Pedro Juan Caballero". Religación. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 3(9), 202-215.

Ortiz Sandoval, L. (2020). "Bases y criterios de análisis de las clases en la sociedad paraguaya". Revista Población y Desarrollo 26 (50): 76-95. http://doi.org/10.18004/pdfce/2076-054x/2020.026.50.076-095

UN (2020). Deforestation has slowed down but still remains a concern, new UN report reveals. UN News– Global Perspectives, Human Stories. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/07/1068761

Ortíz, L., & Rojas, G. (2019). "Elites empresariales y proceso de democratización en Paraguay". Íconos Revista de Ciencias Sociales XXIII (65): 199–220.

Palau, T. (2010). "La política y su trasfondo: el poder real en Paraguay". Nueva Sociedad (229): 134-150.

Riquelme, Q. (2003). Los sin tierra en Paraguay. Conflictos Agrarios y movimientos campesinos. Buenos Aires: CLACSO

Rojas, L. (2014). La metamorfosis del Paraguay: del esplendor inicial a su traumática descomposición. Asunción: BASE-US, Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo.

Rojas, L. (2015). "Historia y actualidad del neoliberalismo en Paraguay" [85-102] in Rojas, L. (Coord.) Neoliberalismo en América Latina. Crisis, tendencias y alternativas. Asunción: CLACSO.

Sotelo Valencia, A. (2018). "Subimperialismo y dependencia en la era neoliberal". Cuaderno CRH 31(84): 501-517. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-49792018000300005

Tamayo, E. (2018). 'Paraguay, repensando la política exterior'. Novapolis 13, 141-162.

Universidad Nacional de Asunción (2020). Soja. Datos, estadísticas y comentarios. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. https://www.agr.una.py/ecorural/cultivo/soja_enero_2020.pdf

Vice Ministry of Mines and Energy (2020). Preliminary report on electric energy. Ministry of Public Works and Communications.

Vuyk, C. (2014). Subimperialismo brasileño y dependencia del Paraguay: los intereses económicos detrás del golpe de Estado de 2012. Asunción: CyP.

|

Sobre la autora: Magdalena López: Licenciada en Ciencia Política y Doctora en Ciencias Sociales por la Universidad de Buenos Aires. Es la coordinadora del GESP en el Instituto de Estudios de América Latina y el Caribe (IEALC, UBA). Investigadora de CONICET con sede en el Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani (IIGG, UBA). Ha realizado investigaciones sobre el rol de los partidos, el sistema de gobierno, la transición, la democracia y el Estado en Paraguay. |